Welcome back!

We have been hoping that you have been missing us but now we are back in style!

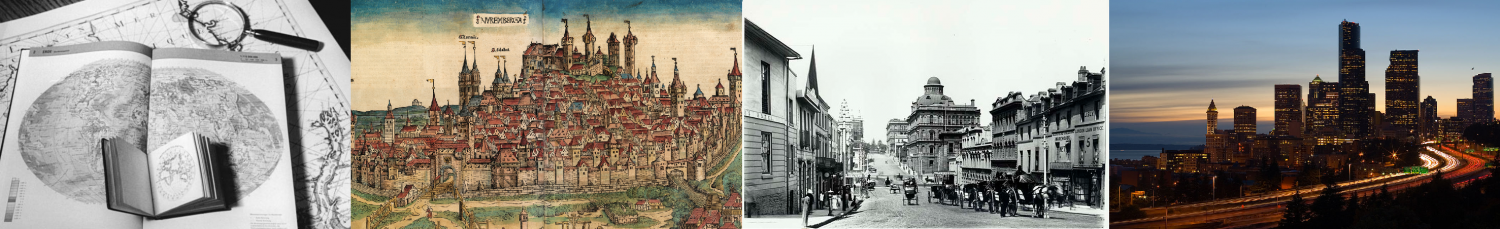

Last week, I explored the city of Rome in Italy with special regard to the use of squares and streets as prime social spaces within a city. This week, I have ventured to North America to the city of New York. In modern days, it is a metropolis of the modern world, a global hub of business. Interestingly, I have decided to step back in time and explore the city of New York in the 19th Century. The 19th century for New York City provided numerous of changes. Major changes in urban infrastructure, transportation and technology revolutionised the city.

Donna|112755861

In 1833, the city established a Water Commission to plan a water supply system. Among the options for the water supply were the Bronx River, Morrisania Creek, Rye Pond and the Croton River. Major David B. Douglass, a hero from the War of 1812 and a West Point engineering professor, supported using the Croton River. Although this was the most expensive option, it could supply 40 million gallons of water a day to the city. The Croton Reservoir was also situated at a high level, so that it could supply the upper floors of city buildings.

Image 1.2 – This bridge, which was completed in 1848, was the first to carry the Croton Aqueduct. It originally had a fifteen span stone arch bridge. This aqueduct brought badly needed fresh water to a growing city. In 1860, the bridge deck was increased in height to accommodate additional piping for more water. In 1872, the distinctive High Bridge Watchtower, which remains today, was constructed to control the water pressure.

By 1825 Gas illumination was widely available on the streets of New York and by the 1880’s had advanced to electric lighting.

Image 1.3 – A change in urban infrastructure such as gas street lighting replaced oil lamps in the 1820s; starting at Broadway and Grand Street. In 1880, the first electric street lights arrived along Broadway between 14th and 26th Street.

By 1897 The Electric Vehicle Company begins producing Electrobat electric taxicabs in New York, the first commercially-produced electric vehicles

Image 1.4 – In 1891, William Morrison built the first electric automobile in the United States. This image effectively portrays the popularity of automobiles. Interestingly, you can also see how two modes of transport sharing the road system in inner city New York, the horse and cart and the automobile.

Interestingly, these new forms of transportation effectively “stretched” the cities out. First, trolleys veered over bumpy rails, and steam-powered cable cars lugged passengers around. Then with the addition of electric streetcars in cities; which was powered by overhead wires. Electric streetcars and elevated railroads enabled cities to expand, linking central cities to the once-distant suburbs.

Image 1.5 – For my final image, I decided to explore the topic of the first elevated railway which successfully linked the ‘suburbs’ to New York City itself. These modes of transportation acted as a social force in rejoining the cities to their surrounding areas.

I hope you have enjoyed exploring these significant changes and the role they played in New York City in the 19th century.

Thanks for tuning in again this week,

I hope you enjoy reading this week’s blog posts!

Biblography:

http://americanhistory.si.edu/lighting/19thcent/promo19.htm

http://www.musicals101.com/bwaythenow.htm

https://archive.org/details/gasilluminationi00bade

http://www.historicbridges.org/bridges/browser/?bridgebrowser=newyork/highbridge/

http://www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/collections/maps/transit/

http://www.nycroads.com/crossings/high/

http://www.searchanddiscovery.com/documents/2014/70168lash/ndx_lash.pdf