” Dobro pažálovat’ “

Hello and welcome to the week’s last blog post; I hope you all have thoroughly enjoyed perusing through this week’s batch of posts!

Last week I examined the regeneration of London after The Great Fire of 1666, this week I have decided to explore the main thoroughfare of the city of Saint Petersburg, Russia; circa the early 20th century. I hope the post will give you a better understanding of main street urban infrastructure as an important public space during this period.

Aoife Cotter | 112495138

Today, Saint Petersburg is filled with rich history and culture, an unusual feat for such a young city of just three hundred years old. The city itself is built upon the banks of the Neva River. Founded in 1703 by Tsar Peter the Great (1682-1721) as his capital; the city remained the capital of the Russian Empire until the Russian Revolution of 1917.

In the late 19th century, Saint Petersburg was thriving. As capital, it was home to state officials, the military garrison and the imperial court. Its unique and dramatic architecture was the equal of any other European city of the time. Buildings such as the Winter Palace now known as the State Hermitage Museum, were representative of a lavish and thriving capital. Saint Petersburg was fast becoming a capitalist city. The effects of industrialization were evident as foreign and national factories grew rapidly within the city’s environs and banks and various other companies made Saint Petersburg their home.

Map 1.1 – Johann Baptiste Hommann’s map of Saint Petersburg circa 1720.

This map depicts the development of the city which was created fifteen years earlier.

The Nevsky Prospect was created at Peter the Great’s behest as the boulevard which would be the main artery to the ancient city of Novgorod but quite quickly became the main street of the city, a city named in honor of Saint Peter. The street itself was named after a 13th century war hero, Alexander Nevsky. Saint Petersburg’s main shops and businesses are located on and around this grand thoroughfare. The Nevsky Prospect, from humble beginnings, has now become Peter’s lasting legacy to the city’s physical infrastructure and its people.

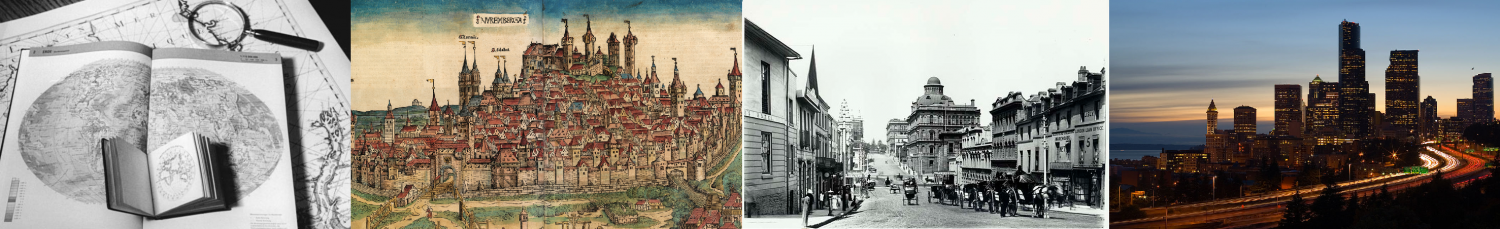

Image 1.1 – The Nevsky Prospect, 1912. This digitalized photograph clearly illustrates the bustling main street and demonstrates Saint Petersburg’s citizens’ use of the Nevsky Prospect in their daily lives.

The Nevsky Prospect continued to evolve throughout the years. In the early years of the 20th Century, the addition of a public light infrastructure and improvements to accessibility, such as new bridges over Neva River, made the Nevsky Prospect a more inviting and accessible public space. In addition to the Winter Palace, the Prospect is home to some outstanding architectural and imposing buildings such as the Kazan Cathedral, the Gostiny Dvor building and The Church of Our Saviour on Spilled Blood which was completed in 1907.

Image 1.2 – A vintage postcard from 1906 illustrates a view of the Winter Palace from the corner of the Nevsky Prospect. This image represents just one of many architectural and historical sites which are situated on the Prospect.

These landmarks enhance the overall experience of the Prospect, they complement the existing buildings of the street which are uniform in nature.

“In the words of the poet Piotr Viazemsky, “slender, regular, aligned, symmetrical, single-colored…””

Image 1. 3 – The Nevsky Prospect; circa 1910. This image clearly illustrates the Prospects success and popularity as a main street in the early 20th century and demonstrates the uniformity of the streetscape architecture.

Today, the Nevsky Prospect still exists; it is the city’s central shopping street and the hub of the city’s entertainment and nightlife. It still possesses the same function, it did in the centuries before; acting as a place of promenade for citizens and tourists alike.

“‘Public space’’ is the space where individuals see and are seen by others as

they engage in public affairs” – (James Mensch, 2007)

While the Nevsky Prospect is not a public place of recreation, it is a public space of importance and innovation as a functioning main street. In the late 19th and 20th centuries, it was the city’s central hub of activity, a space that allowed business and trades to thrive. Its significance and success as a crucial urban structure is supported by historic photographic evidence, some of which is included above.

Image 1.4 – The Nevsky Prospect circa the early 1990’s. This image is yet again another representation of the avenues success in the early 20th century.

Image 1.5 – The Nevsky Prospect; modern day. Its function in society has not changed since its foundation.

While, the other contributors to this blog have examined various other processes which occurred in cities throughout the 19th and 20th century. I firmly believe in the importance of public space. The utilization of public spaces has been established for centuries and many historic public spaces continue to act as hubs of activity in today’s society. The Nevsky Prospect is a perfect example of such a functional public space; it provides both a platform and focus for the city’s daily operations and interactions and facilitates its citizens and tourists alike.

And with that concluding sentence, I bring this week’s blog posts to a close.

Be sure to stay tuned for next week’s blog!

From Russia with love,

Bibliography

The Facts of Saint Petersburg – Available at: http://www.saint-petersburg.com/quick-facts.asp[Accessed 21st October 2014]

Saint Petersburg History – Available at: http://www.saint-petersburg.com/history/introduction.asp [Accessed 21st October 2014]

Saint Petersburg History – Available at: http://saint-petersburg-russia.org/st-petersburg-19th-century [Accessed 21st October 2014]

Nevsky History – Available at:http://nskrip1.blogspot.ie/2012/11/the-history-of-nevsky-prospect-in-st.html [Accessed 21st October 2014]

1720 Map – Available at: http://www.raremaps.com/gallery/detail/31239/Topographische_Vorstellung_der_Neuen_Russischen_HauptResidenz_und/Homann.html [Accessed 21st October 1014]