Bonjour et Bienvenue!

“You can’t escape the past in Paris, and yet what’s so wonderful about it is that the past and present intermingle so intangibly that it doesn’t seem to burden.” -Allen Ginsberg

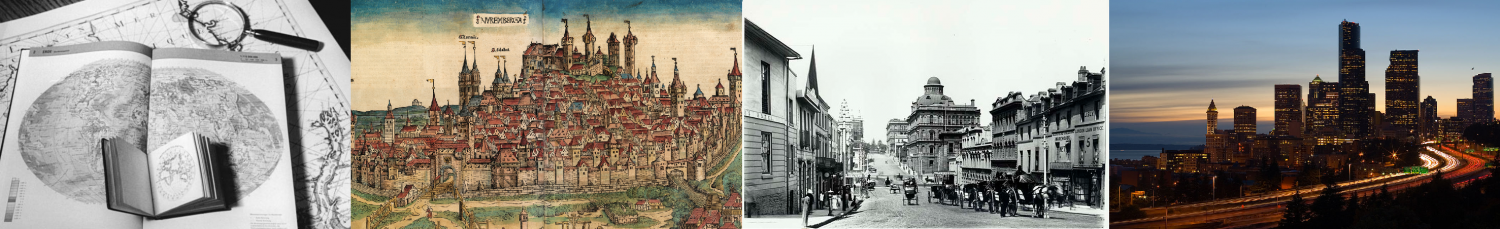

For this week’s blog entry, I’ve decided to be self-indulgent and use it as an excuse to learn more about, and to then share with you, my favourite city, Paris. To date, I’ve been lucky enough to see some awe-inducing parts of the world, but none are quite like the French capital of Paris that has been hollowed and re-fashioned by history. As one walks through her boulevards, you’re captivated by something new at every corner, but it’s the seamless juxtaposition between the old and new that is most brilliant.

This week I shall be focusing on the modernizing of Paris during the Age of Enlightenment. I intend on doing this by comparing, with the aid of digital maps, pre and post Baron Haussmann’s endeavor to undertake one of the largest urban regeneration projects since the burning of London in 1666 which you can read more on in Aoife’s first installment.

Haussmann’s radical project included such things as an expanded sewer system, gas lighting for the streets, a uniform facade for the city’s building, construction of new parks and the division of Paris into arrondissements. However, for the purpose of this blog, I shall focus in on the construction and reorganization of boulevards across the city. “Think about Paris and sooner, rather than later, the word boulevard will come to mind. Boulevards – the word itself, perhaps as much as their physical reality – define this city. The word conjures up images of broad tree-lined sidewalks, elegant building, attractive stores, corner cafes, crowds of people, and the warm light of street lamps.” (Jacobs, McDonald & Rofé, 2003)

Image of The Avenue des Champs-Élysées which is a boulevard in the 8th arrondissement of Paris, 1.9 kilometres long and 70 metres wide, which runs between the Place de la Concorde and the Place Charles de Gaulle, where the Arc de Triomphe is located. The grandeur and width of this boulevards and nicely complimented by the manicured trees and large open spaces at the end of each boulevard.

Fig. 1: A Plan of the City of Paris, 1800. Source here.

As seen in the map above, the streets used to be narrow, chaotic and disorderly, leading to everywhere and nowhere. The tight confines of medieval Paris were hindering the city’s potential for growth and its desire to transform into a well-organized, modern urban hotspot. Modernity’s urban signature was seen as one of order, power and transformation. For Napolean III, that is exactly what he wanted to gain over the Parisiennes: control; boulevards were a physical representation of just that. Although many people at the time argued that the sole motivation for the construction of these boulevards was a strategic move by Napolean III and his military, Paris urban historian Patrice de Moncan wrote: “To see the works created by Haussmann and Napoleon III only from the perspective of their strategic value is very reductive. His desire to make Paris, the economic capital of France, a more open, more healthy city, not only for the upper classes but also for the workers, cannot be denied, and should be recognised as the primary motivation”. They were the places to see and be seen; lined with opulent boutiques, café bistros and hand-manicured trees. They were places where affluence could be flaunted and admired, and where, thanks to the new water and sewer systems, citizens could show off their new found cleanliness.

Fig. 2: Snippet of Map of Paris, 1800. Source here. Fig. 3: Snippet of Map of Paris, 1889. Source here.

Even though it’s quite hard to believe, Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 are of the same location in Paris, just west of the Ile de la Cité. This contrast between the 1800 and 1889 maps illustrates the extent of Haussmann’s transformation of the city’s street-scape over a mere time-span of twenty years with examples such as Boulevard du Temple and Boulevard de Ménilmontant shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 4: “Before Haussmann” Map of Ile de la Cité, Fig. 5: “After Haussmann” Map of Ile de la Cité,

Paris. Source here. Paris. Source here.

Another visually striking contrast of pre and post regeneration evident on the Ile de la Cité with the development of wide, traverse roadways across the island joining the two bank of the Seine.

The revamping of Paris’ streets into boulevard was, I believe, an integral part of bringing the City of Light out of the Dark Ages and into the Modern era.

Thanks for tuning in this week and sticking with me! Hope you’ve enjoyed my very first blog post, as well as the others!

—

Jennifer E. | 112302041

Planning on doing some offline perusing? Download the ePub!

References

Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3 – Old Maps of Paris. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.oldmapsofparis.com/. [Accessed 15 October 14].

Fig. 4, Fig. 5 – Ile de la Cité transformation. [ONLINE] Available at: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Paris-cite-haussmann.jpg. [Accessed 15 October 14].

Jacobs A. B, McDonald E. and Rofé Y, 2003. The Boulevard Book: History, Evolution, Design of Multiway Boulevards. MIT Press.

de Moncan P., 2002. Le Paris d’Haussmann, p. 34.

General information on Haussmann’s plans. Available at: http://www.arthistoryarchive.com/arthistory/architecture/Haussmanns-Architectural-Paris.html [Accessed 12 October 14].